Why allow others to tarnish your words;

To harden your message;

To encase and package it;

To narrowly channel it,

Into an empty shell?

A mere qawqa3a;

Where the living being crawled out long ago.

A shell of what it is.

***

Writing as a stream of consciousness. Exercise done at a workshop by Writers Ink in May 2011. After reading a poem by Muhmoud Darwish, we were asked to write with the title ‘I long for…’.

Evidently, I’m no Mahmoud Darwish, but wanted to share nonetheless, as with recent attacks done in the name of the religion that expresses my faith.

Qawqa3a

The life you inspire into me,

I complicate.

The health you bestow upon me,

I disregard.

The food you offer me,

I limit.

The senses you sculpted into me,

I dull.

Yet I utter your words every day,

I sing your praises hourly,

I breath your presence constantly,

My beloved.

The Giver of Life, the Taker of Life.

Al-Mu7ee, al-Mumeet.

Al-Dhahir, al-Baatin.

Al-Awel, al-Akhir.

I am embedded in your cycle;

Your balanced polarities.

Intertwined in your design;

Your sealed book.

Struggling with the questions you posed.

Show me:

What is in my heart?

Tell me:

Who am I?

Must I wait for the Day of Judgement?

Must I leave this world,

Before I have understood it?

To ask;

To seek;

To ponder;

To reflect;

All because I long to understand you,

My beloved.

Why allow others to tarnish your words;

To harden your message;

To encase and package it;

To narrowly channel it;

Into an empty shell?

Qawqa3a;

Where the living being crawled out long ago.

A shell of what it is.

You, who is beyond all human judgement;

You, who knows what is in my heart;

Judge me.

Weigh me.

Lift me.

Reveal yourself to me.

My trust is in you,

And in you alone.

Pour into my heart,

And let me feel you.

I long for you, my beloved.

I’ve been asked a couple of times recently, if my life has taken on a ‘deeper meaning’, now that I’m a mother. I’m never quite sure what to say, so as not to seem uncaring or ungrateful. Of course, my daughter is not only the most important part of my life, but my current situation dictates that my daughter is my life. Yet, I’m not sure I can say my life has become deeper or richer. If anything, my current world is incredibly small, and as it centres around an infant, it is actually pretty basic too.

‘I needed to do something so I can breath’, said entrepreneur and social activist, Rashma Saujani, as she addressed us at Creative Resistance last night. She sat, with her toddler on her lap, and spoke of her involvement with the Women’s Marches here in the Bay Area: ‘I didn’t want my son to grown up believing this is OK.’ Others spoke too and acknowledgement was given to the various women present, who all led marches in particular cities. All with impressive turnouts.

For the first time in a while, I was very clear about why I was there and what I wanted to do. Last week, I envisioned leading one or more gatherings with those directly impacted by the so-called ‘Muslim Ban’, such as myself, and those who aren’t, but are curious to attend. The intention is to create a space to share experiences, stories, ask questions, show support, connect on a basic human level in the here-and-now, rather than get lost in the heady politics.

Since the ban, some expressed surprise: ‘I didn’t know that I knew someone directly effected by the Ban!’ Sharing my current status with my mother/baby group last week (luckily I changed groups!) invited support and apologetic statements.

Hence the gatherings idea: so people can connect on a deeper level, feel a sense of validation and receive the healing that comes with making contact with other human beings.

With no idea what to expect yesterday, and running some 45minutes late, I nervously walked into a large, trendy open office area, with booze and popcorn dotted throughout the space, boards with idea plans, screens with projected images, bowls of badges with attractive feminist logos. The people present were a mix of social workers, artists, therapists, young techies and entrepreneurs. Rashma herself set-up Girls Who Code, so even your average start-up-y is not average, by virtue of being a woman! Most of those present seemed out of place in this part of the Bay, as opposed to trendy Mission, so I drank every bit of this buzzing energy.

Spoke to three people about the gatherings, and all, with typical American can-do attitudes, were full of beans for the idea. Right now, it’s an idea, though I do want to realise it into a something somehow pretty soon.

Last night, I got the support I wanted, and I left on a high.

I said that this isn’t my battle, and maybe it’s not. I do want to look back one day, with my daughter, and say: our time in the US was brief, but we were part of this incredible movement!

I didn’t even make the march in SF, and I’m not sure why exactly, as I was aware of, and anticipating, it. The domestic mommy bubble can be pretty all-consuming.

On a deeper level, the instinctive reptilian responses to trauma are fight, flight or, sometimes forgotten, freeze. Maybe, with the blow of Trumpy and the Ban, I’ve been frozen, feeling stuck and numb. Stuck emotionally, as well as geographically. Being amidst the women yesterday, I felt a thawing. A stirring of potential.

A witness assures us that our stories are heard, contained, and transcend time.

Last time I said it’s not my battle, and I’ll only be a witness. Though for a moment, I forgot the imperative role bearing witness can be in the process of healing.

I’m moved by friends expressing words of concern and sympathy with the latest US movements. Thank you.

‘Tara: sorry we have a giant orange piece of shit running the country. Hope this madness doesn’t end up affecting you. As an American, this is embarrassing.’

As much as I’d like to lay all the blame on Trump, to me, this is not new or shocking. As a British-Iraqi, I’ve already been marked out and denied the visa waiver I had been entitled to as a British Citizen (ranted about it here). And that was under Obama. This seems an ugly extension of what already began under the last administration.

And I’m with Omar Kamel, who suggested many Arabs were glad to see Trump’s vulgar in-your-face attitude and actions come to the fore; as this longstanding attitude is simply being made glaringly visible to the world. America has always put America first, but now, it’s doing it loud and proud. The facade has fallen.

‘Thinking of you, given the extraordinarily nasty immigration restrictions that just came in – are you in the U.K. or US (or somewhere else) at the moment?’

I’m in the US, largely at home with a new baby, in a quaint, white, affluent neighbourhood in San Francisco, which feels as far from Trump’s America as possible. I am mostly in contact with darkly positive, competitive, double pumping mums, who juggle start-ups and Baby Bootcamp in Lululemon gear. Very, very far from Trump.

‘I’m so angry, and I feel so helpless, I want to go on every demonstration I can! And she [Teresa May] is a witch bitch!’

I’m not angry. Or maybe my anger had been suppressed for so long, it’s turned cold and passive.

Again, Trump can’t take all the credit, as our very own unelected Teresa is openly complicit. Yet again, unsurprisingly, Britain is the US’s loyal bulldog. What’s new?

My community work was all about exploring and facilitating the process of integration for migrants, and creating a space for dialogue between people of difference, to allow diversity to thrive. In the U.K., I would be hitting the streets, setting-up a gathering, meeting with friends. Here, I’m a guest who’s landed in a home undergoing a crisis.

Right now, I’ve no intention of setting roots here. I respect the battle some are gearing up for, and I want to say: this is not my battle to fight. I am only your witness. Right now, what I am witnessing includes waves of support, beautifully articulated and diversely expressed anger. Those who had taken their values for granted, are standing up to defend themselves and others. This, for me, is a big part of the current picture.

‘I’m wondering how you are feeling and how you might be affected by the insane and unbelievably destructive immigration ban in the US at the moment?’

I feel sad, and somewhere I feel angry, for those whose lives depend on the US. Some have literally had their lifeline cut off.

For me, I’ve desperately looked forward to family visiting. If they can’t come, then I would want to leave. And if I can’t come back, then I’ll be grateful to have (once more) fled a battleground.

Two months after I gave birth, I moved from the UK to the US, to live with my partner in California. If you imagine sun, sea and surfing, then I should say, I’m in Northern California, and in the notoriously cool and windy microclimate of Pacific Heights in San Francisco.

After being here for two months, I have yet to make a single friend. This is unlike me, as I usually relish throwing myself into new and challenging situations and groups. This has not been the case here.

Instead, I miss home; my friends, the familiarity of London, my cat, bicycle and overall, the various networks I tapped into for emotional support, work opportunities and play. Here, I’ve largely been in a lonely bubble.

Add to the mix the postpartum hormonal fiesta, and the speed in which so much has happened in the last year, well, I’ve landed with a thud.

We are staying in a pretty pink cottage, in a posh part of town, people seem friendly, our neighbours have been kind and welcoming, and most important, being together as a family is truly a blessing. And yet, here I am, with a sticky stuck feeling.

As a new mum, life’s focus whittles down to one important (little) person. Everything else fades into the background. Without the traditional system of family and community nearby, then this can be very isolating. The world shrinks, and can feel a pretty lonely place.

As much as I love being with my beautiful baby, I sometimes wish I had work to go back to (!), adults to engage with, the satisfaction of working uninterrupted on a single task, and the appreciation of a job well done! Alas, until I tap into relevant networks here, I’ll be home, and discovering that being ‘full time mum’ or ‘homemaker’ (what a title!) is hardcore. The mothering bit is a pleasure. It’s the other bits that grate.

Becoming a mother is one recent, and tremendously important part of who I am now, and it’s one part of me. In London, where I had people and structures already built, I felt connected. Not only to others, but by being with those who know me, I stayed in touch with who I am beyond being a mum. I felt together and whole.

Here, my identity first and foremost is of mother and wife- both relatively recent phenomena- then alien, on both counts of being British and Iraqi.

In our neck of the woods, the corporate, tech and managerial worlds rule. Though not too far there’s a lot of the community/ therapeutic/ creative spirit I’m craving. Yet I’m struggling to make time beyond the domestic sphere I’m inhabiting.

I’ve written about developing a ‘sense’ of self and belonging, and maybe this is what I’m missing: in my shrunken bubble, it’s been hard to fully immerse my senses into my surroundings.

When motherhood came into my established life, it was a new layer to a pretty solid foundation, and I was able to begin the process of integrating this new phenomenon into what I already had. When all this shifted, and I carried myself and baby somewhere altogether new, I’ve only had newness and little by means of an anchor to hold onto. Both my inner and outer worlds dramatically shifted. And continue to shift.

Whilst in transition, I’ve sometimes felt like I’m breaking down.

Gestalt therapy proposes that there is no creation without destruction, and the ‘self’ is continuously being created and destroyed. This takes place when in relation to the environment and ourselves, be this the physical, social, emotional. In order to create a new picture, the old one needs be broken down. I’m holding onto this.

Only The Lonely is (I hope) my temporary state, and I need to trust at the end of the this destructive phase, something deeply sincere and beautiful will emerge.

I’ve taken for granted that I’m a feminist. After all, can I, as a woman, expect equal rights as men, and not be a feminist?

Though I’ve often secretly thought of myself as an ‘Eastern Feminist’, as I’ve come to believe life is not simply about an equal share, but a fair share. Sometimes these are one and the same, and other times, these are distinctly different. Learning to recognise the latter is key, and having the courage and will to stand my ground is second.

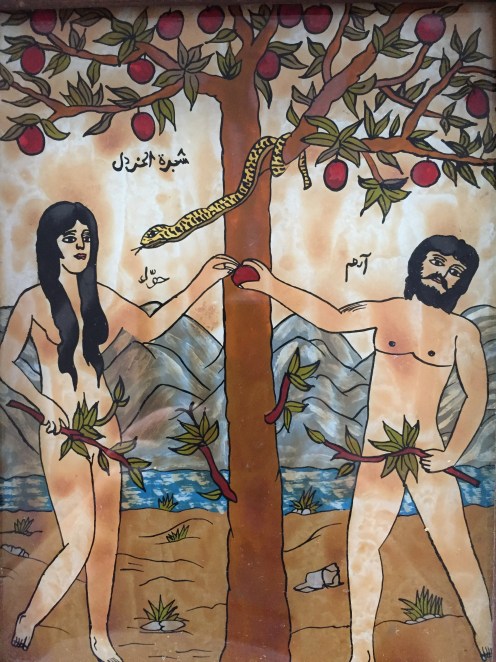

Above: Adam and Eve with the Tree of Life.

For me, it’s not about splitting a cake in half regardless of how hungry I am. If I am mildly peckish, and my fellow man is famished, then I would be content having enough to satisfy my hunger, whilst he quells his. Rather than insisting on an equal half, when I don’t need as much and likely to leave my share to waste uneaten.

This relies on sharing with someone who would not interpret my giving him more than half as weakness or stupidity. If I’m famished the next time, then he needs to allow for that too, and accept that I may want an equal share, or even, more than half.

The issue here is difference. I am different to a man, and deserve to have this recognised and respected. My body can bleed once a month and produce a human being. A man cannot. Statistically, I will live longer than my male partner, and physically, he’s stronger than me. That’s not to say all men are stronger than women, or all women can or want to have children biologically. Yet bypassing this difference can eat into the beauty of who we are, and rather than bridging differences, we risk burying our essence in sameness.

Now, I believe unequivocally in equal pay, the right to vote and such basic human rights. And today, when I am caring for my newborn, whilst my partner works at his day job, I cannot deny we are doing different things with different challenges and rewards. To say these are the same is inaccurate, and I would say, insulting. My ‘work’ is 24/7- the term ‘full time mum’ has come to hold very literal meaning these days- and yet that’s not to say it’s any more valuable or demanding than his work.

If we recognise and respect our current roles, and give equal weight to each, then we are better positioned to support one another. If he just sees me as a glorified maid, and I see him as a money maker, then eventually, something is bound to give. I can work, and may choose/ or need to again in the future, and he may want to try taking an equal portion of our child’s care, but this is what we have chosen to do for now.

So by ‘Eastern Feminist’, I shift the focus from two of the same, to two different shares satisfyingly balanced. Yin and yang relies on recognising the beauty and validity of each. God’s 99 Names often refer to opposing qualities, which to me imply equal importance of death as death, or constriction as expansion.

I am both different and equal to you.

Much of this is of course cultural, and follows what we identify as desirable and acceptable ways of being.

I’ve met feminist women in bright red lipstick and hair down to their hips, who delight in receiving jewellery and meals bought for them by men. And men who claim to be champion supporters of women’s rights, justifying the services of young prostitutes whilst on holiday abroad. To me, these stand out as contradictions.

Meanwhile, as I settle into motherhood, it’s becoming clear to me that embracing this role full time is not given the same weight as working in a job. This I find sad as it implies a form of devaluation of what it is to give yourself to motherhood. Nonetheless, I will continue to explore, with my partner and infant, what we need and exercise my right to choose.

At a ‘Yin and Yang’ yoga class today- combining dynamic, fast and vigorous Vinyasa alongside gentler poses, held for longer- it seemed the difference between the two characters defined the session as a whole.

I now sit with the difference between compatible and complementary, particularly in relationships, romantic or otherwise. I often hear a desire for compatibility, and I relate to this as the implication is that there is enough similarities between you and me, so we get on steadily, smoothly and with minimal conflict. However, I have often been attracted to those different to me, be this cultural, professional or otherwise, as these differences somehow allow for a sense of completion in one or more ways. In other words, the relationship feels complementary, precisely because of the two different elements, which when combined, have the ability to emphasise and enhance one another.

In marriage, my parents were as seemingly compatible as can be. Their characters are similar (grounded, intelligent, pragmatic and appeasing), their interests (all things original and innovative) and tastes too (from food to furniture!), they shared one nationality, similar family backgrounds and theirs was a pretty small community in Baghdad in those days; they were both well travelled (before they even wed) and educated in both Iraq and overseas yada yada… you get the picture. Their union did not last five years. There was no dramatic affair, addiction, or such story. For subtly complex reasons, they parted ways with a relatively amicable divorce. Yet by its nature, the parting was painfully and humiliatingly public, particularly as divorce wasn’t as common nor normalised as it is today.

As a child, I used to imagine my parents couldn’t stay together because they were like magnets of the same charge; unable to stick together. Anything else was hard to imagine, as I’d never heard either speak ill of the other, and seemed to get on exceptionally well.

Meanwhile, my grandparents were decidedly chalky and cheesy in their differences, and somehow managed to make their romance last for over fifty years. They had their disagreements, with pretty tempestuous arguments in their youth, and visibly struggled to accommodate their opposing perspectives and attitudes. They bickered on a daily basis. My grandfather would say things like: ‘Just as our prophet was divinely inspired when he received his revelations, I believe Mozart was too when he composed his music’, to which my grandmother would interrupt with: ‘Please keep your opinions to yourself!’ He prayed and fasted, she didn’t. They joked and laughed together (serious belly laughter!), travelled regularly together and recited poetry to one another well into their 70’s.

There are many reasons why relationships last and just as many as to how they might fall apart, though right now, as I reflect on my partner and friends, I am grateful for our differences, as well as our commonalities. If it was all smooth and easy, how would we be challenged? Would we sincerely grow and develop together as individuals? Of course, differences, if not addressed, can also fester and rip an otherwise, peacefully artificial facade. That’s where the effort comes in, the building of trust to hold and contain, negotiations and communications, allowing conflict to energise and move forward rather than quietly stagnate.

As Ramadan approaches, I recall how my grandfather defended my grandmother, when I asked him why she was the only member in our household who did not fast during the Holy Month: ‘how a person chooses to practise their faith is between them and their Creator, and not for you and me to judge’, then he added, ‘it’s her skill, care and love that creates the most inviting home and atmosphere for us to break our fast. Plus, she has to put up with our tired, drooping faces all day!’ There was utter respect and acceptance of difference.

My memory of them today is of an elderly couple, sitting on their balcony in Ras Beirut, where they retired, watching the sunset in silence. Together and apart.

***

I wish everyone, a harmonious, deeply reflective and attuned Ramadan, where I hope thoughts and prayers are sent to those in the Middle East, and across the world, struggling for the simplest morsels of life.

Being present, some meditating yoginis would have you believe, is equivalent to being positive. Let go of the past, only carry positive feelings towards the future and all will be well in-the-moment.

Nonsense.

Admittedly, I’m someone most comfortable sitting in zones of grey, rather than at any one end of an extremity. This includes binary divisions of positive/ negative, good/ bad, happy/ sad etc. If I heard someone express hope towards, let’s say, a better future, then I automatically hear undertones of someone who may have tasted a lesser past, or at least would like to avoid reliving something. This isn’t good or bad, it just is what it is.

To reject a feeling I deem negative, say hurt or concern, is to narrow my self-awareness, to confine myself to an imagined way of being rather than embrace whatever the present actually has to offer. If not, I risk dividing myself into fragments, some of which I keep and others I creatively reject, ignore or numb through whatever means. Reality will come back to bite in the backside. Mark my words.

It just is what it is, amounts to: I am what I am, and all that I am, right here, right now.

And it’s not all about me/ you, because this rejection extends to others.

Common knowledge to Brits of Iraqi, Iranian and Syrian origin, are changes to the US Visa Waver program; namely, those who are dual nationals or who have been to these countries post-2011, other than for ‘diplomatic or military purposes’, will not be entitled to wave away the US visa application process. Dual nationals, having checked this out with the US embassy, need not mean owning a valid passport to these countries or having recently visited, but simply if you are born there, and in some cases, if you belong to parents born in Iran, Iraq or Syria.

Initially, I didn’t think much beyond the mild inconvenience of this change, knowing I’d need to apply in order to visit my (British) partner next month. Though waiting for an hour and a half (after my scheduled appointment), outside the US Embassy yesterday, I had plenty of time to reflect. Am I less of a British citizen than other Brits? Am I now a second class Brit? I felt firmly in the latter categories, assuming the British government- my own government- would have needed to approve such a change in policy. I felt unprotected, handed over by my own guardians to another’s discretion.

As I waited in one of three queues, I had an unfamiliar sense of entitlement rush through my body: I am British, I should not be here! It was doubly humiliating, chatting to others in the queue (Nigerian, Argentinian, Chinese and Malaysian) when they noted my accent, and some spotted the precious red passport in my see-through plastic envelope: ‘you are British, why are you here?!’

This sense of entitlement was juxtaposed by a much more familiar feeling of 1) anxiety, particularly in relation to the official interview- when nervous and confronted by figures of authority, I come across as incredibly dodgy (!)- and 2) compliance and acceptance. Both these are a residue of the Iraqi in me, particularly one raised under the Ba’ithist regime, or maybe more generally, developing country’s make-do attitude. I’m lucky to be in this country, I shouldn’t ask for more. Though I seem to have grown more British than I had imagined, because I do believe I deserve the rights I am promised as a fully fledged Brit!

My anger is not related to the inconvenience of queuing, which in itself is pretty harmless. This is a matter of principle: I have done nothing illegal or suspicious, to be signalled out and treated discriminately in this way. This is happening because of my birthplace, my origin and past, which presumably had been accepted and legally integrated as part of my British identity when I received my passport in 2001.

I appreciate the security threats and the refugee/humanitarian crisis, but this discrimination and alienation of Brits and Europeans minority groups cannot be a sensible solution. I can accept it from foreign countries, like waiting for some eight hours at the Jordanian-Israel border last December. Or when I had my Iraqi passport, I accepted lengthy visa processes (and rejections) from various Middle Eastern countries like Jordan, the UAE and Lebanon, as well as America and Europe. Today, my British-Lebanese friend, who has been in this country for half the length of time I have and who only received her passport last year, has more rights than I do. There is an injustice here that can be damaging on a wider social level.

My community work centres around the concept and process of integration, both personal and social. The personal encourages an individual to develop a sense of inner wholeness, particularly in relation to the different (and often conflicting) parts of her identity, e.g., Iranian origin, woman, lesbian, Muslim, socialist, pub goer, dog lover, Londoner etc. Embracing these as part of a rich and unique perspective, allows the person to be at peace with themselves, and by extension, the society they live in. Social integration is the latter, the practical and emotional ability to live side-by-side with the majority with a strong sense of belonging as part of the whole. This, as opposed to isolating herself from the majority, whilst sticking to fellow minority groups, and feeling disconnected from the whole.

That fractured existence, both on the personal and social level, I believe, makes easy prey of those young Brits (and Europeans) easily plucked and groomed towards ‘radicalisation’ by militant extremists. Those lost and misguided are lead to believe they belong, not in the country they were born and raised in, but in a foreign country. Joining a devastatingly fantastical battle between ‘them and us’ is essentially who they are, and who they should be, as they will never be accepted as part of British society. This is not just me ranting, the systemic failure to support such communities, particularly second generation migrants, has now been documented to contribute towards their demise.

Now, I’m not personally under any risk of being ‘radicalised’, and and still I wonder: How am I meant to feel integrated, as a first generation immigrant, when I am isolated from the majority and labelled under my subgroup? Why is this OK? Would it be OK if I was signalled out for being a woman? Or gay? Or Muslim? Erm, scrap the last category, as that’s already presumed in the list of countries declared dangerous…

I imagined, when I headed to the US embassy, I would go through a slightly different process, presumably as they may require more subtle security checks and more in-depth interviews, for ‘nationals of VW countries’. That I may also have accepted somehow; special cases with special treatment. This was not the case. In the end, I waited for over two hours to have a 5-minute interview, standing whilst facing an American woman behind a glass screen, with another person in the queue inches behind me. Every person I met, from security guards to this lady behind the glass, were polite and efficient. Though as I said, this is a case of principle not mere practicalities.

To the British government, I ask: how can you hand me over after you accepted me as one of your own?