Been waving in the last few weeks between excitement and anxiety, as I prepare to leave for IamResilience, a creative-therapeutic pilot project working with children and women in a Syrian refugee camp in Lebanon. There’s generally very little for me to go by in terms of regional case studies, mixing the creative arts with therapy, where the work is not artistic, for example, I don’t leave with a play or a film to show, and neither is it therapy per say. The intention is helping to relieve a portion of the anxieties these dislocated peoples would have gone through, in finding themselves in a refugee camp… actually no, it’s not even to deal with the traumatic events, it’s to begin with their current state of being in a refugee camp. I expect to work with healthy people who have gone through traumatic experiences, rather than psychologically traumatised individuals. I’m not interested in talking about the project itself- I plan to write shorter blogs on the Meryna website as I go along- what I do want to share are a few reflections on the therapy training, and my personal unpacking, that have come to mind recently.

First, thinking back to Laura Perls quote: the difference between anxiety and excitement is breath (something along those lines). I’ve been reminded of this fine line between the two states, and how both have been valuable to acknowledge.

Second, noticing how I have approached Ending my time in London- I’m away for three months and a half, so it’s not forever (hopefully!)- and reflecting on the Gestalt therapy training from last year, particularly with our therapist/ tutor Kay Lynn, who dedicated ample time and space for Ending our year of the course. At the time, initially at least, I thought it excessive; this was after all a one-year course, that was coming to an end, and that was that. I had done what I always did with endings: gone to the future. I was thinking of what I will be doing next, planning ahead, and generally looking forward, whilst Kay Lynn saw this as opportunity to notice how we deal with endings. She strongly invited the class to stay present, to find ways that help us commemorate the end before welcoming a new beginning.

This is where I have been- with a varying degree of awareness, and largely intuition leading this process- I’ve noticed I have done things I would never have done a few years ago. Making sure I finish business as much as possible, from my work commitments of setting-up Meryna, completing art and freelance work to fixing a broken loo! Making time to meet friends and peers, to catch-up, and even having a leaving-drinks at a local place for a small group of friends… this is all very new to me. I don’t even celebrate my birthday collectively, with any group of people, let alone a work trip abroad!

So in reflecting on this, I feel that only now, on the day I am departing, I am beginning to look forward. Of course, I have been preparing for the future, in terms of consulting with project partners in Lebanon and specialists here, my therapeutic supervisor and the supervision group, but this is different. Staying present for me has been about a coming together, collecting myself, before leaving. I feel appreciative of these rituals, societal and personal, which help commemorate endings and welcome new beginnings.

At the last Gestalt therapy residential weekend, where much of the Ending work happened, I had a mini-collapse towards the end. After deflecting and resisting, I touched on the lack of any form of commemoration in leaving Iraq, my first home. That ending was never acknowledged at any point, before leaving (we’d not planned to stay in the UK) nor after arriving (not knowing if we will be staying for the first five years or more!). Our process, as a family, was just to move forward, and I believe that’s what was needed at the time, and yet it is amazing to be able to acknowledge that now.

Of course I think of the people I will be meeting in Lebanon, and if my ending with my homeland was abrupt, then what must theirs have been like? And I wonder how the therapeutic work will be around this lack of ending, and reflecting on a more stable time; remembering the rituals and commemorations that formed part of the norm (individually and collectively) and what has remained. These things that help make us who we are, which have since been displaced.

I’ve just been reminded of the importance of identifying what is working well, in context of IamR, not simply what has been lost or the difficulties of life at the refugee camo. This reminder came from Renos Papadopoulos, who has generally advised and informed the proposed plan for IamR. Renos’s incredible work emphasises the range of responses to trauma, particularly associated with forced migration etc., and to remember that refugees are essentially people who have been dislocated and are in the process of relocation. Their responses as individuals will be as rich and diverse as yours or mine would be… this all seems incredibly basic, and yet so easily forgotten.

So now, I’ll make my second cup of tea of the day, and carry on with my pre-travel chores.

Loving this rainy London weather, as I know I will miss it in South Lebanon’s scalding and humid summer heat!

Struggling to work a ticket machine at the airport, I asked a man for help. Turned out he had a spare ticket to the nearest underground station, and was in a rush for a meeting, so we rushed together to catch the train. Chatted on the way, mainly on cultural differences and London life, and parted ways with: it was sincerely wonderful to meet you.

He could have asked me out, and this would have been a romantic story. Alas, he didn’t. Nor had I thought of the possibility at the time.

It was the sheer joy of connecting. The world seemed that little bit smaller, closer and more together.

I spent last week at an annual meditation workshop in Madrid, and in a post-session snack one evening, two friends (Delphine and Laurie) and I set ourselves a challenge:

Who can speak to more strangers in the coming year?

This was rooted in discussing whether or not to connect with people on public transport. Laurie shared his fruitless attempts on the subway in New York, compared to Delphine’s lack of attempts on the metro in Paris and then my rare and random chats on the tube in London.

We discussed how we’d collate evidence of our meetings, and what constitutes a connection- does my having a transient greeting on my bike to a pedestrian, or fellow cyclist, count? No, according to the majority. So a conversation, a connection, that’s the challenge.

Ironically, a Spanish woman, a stranger, in the very place we were eating, came to ask us who were and what we were doing in Madrid… and this lady ended up attending the next two days worth of workshops with us!

And like a seed, this intention came into fruition, soon as I hit UK soil.

I’ve spoken at length to another stranger yesterday, at a random snack bar in Shoreditch, where I was grabbing a plate of rice and curry for lunch… this time we chose to exchange contacts, as our professional worlds may have overlaps…again this felt good.

At the same cafe, I talked to the lady who cooked the curry, at the same cafe, who told me about her love of farming on her allotment, and how 16 of her beloved chickens were hunted in one night by a stealthy fox…turned out that she runs two charities in Thailand for blind people and elderly women, and I could have spoken with her for a lot longer, had I not chosen to run (well, cycle) to a meeting, so I promised to be back again soon… and I will be.

London felt nothing like the vast and lonely world I had originally gotten to accept. As people- as animals!- we want to connect. I want to connect.

Also yesterday, a woman working at reception, told me how she felt shaken after an incident at the weekend: her mobile phone had been snatched from her hands, and how no one from the busy street even dared look in her direction. That’s the kind of interaction with strangers that I hear more about. Didn’t dare share Talking to Strangers challenge.

In fact, when I first moved to London to live with my mother at my grandparents’ home, I was pretty much scare-mongered into avoiding any contact with strangers: “People will kidnap and rape you in broad daylight, and no one will dare come to your rescue!”

I accept that my grandparents were strangers themselves to London, and in turn, London was a strange place to them, so they needed to protect themselves, and wanted to extend that protection to their family.

Still, I exercise caution, and I want to explore ways of bursting my individual bubble. Less on the underground or bus, as I have mentioned, I’ve become a keen cyclist, so I rely on other random encounters.

Please know, I do not go out of my way to talk to strangers. Far from it! I just keep open to the possibility of mutual connection.

There’s still the question of evidence: how will I prove that these interactions really happened. The thought of asking the man I met at the airport to pose for a selfie crossed my mind, but I didn’t have the bottle to implement this genius idea… other ideas are welcome!

Thinking about how to listen to minority voices, and by minority I don’t mean what’s defined as ethnically, religiously or culturally a minority in the UK, but a broader definition of minority to mean people with opinions or beliefs that do not conform to the wider society. Specifically, those who believe: foreigners are scroungers, rude with no manners, take our homes and jobs, can’t speak English etc. These are the people we, as a society, need to listen to, and I will explain why.

These particular comments were listed on a slide, part of a talk at a conference I just attended at Centre for Social Relations at Coventry University. The speaker had researched a particular area in the UK (to remain nameless here), interviewed two groups of people: white working class and Muslims (possibly an odd categorisation, but let’s skip past that bit too for now). Without going into the study itself, these quotes stood out for me. I saw these are as experiences, stories, even facts, in the perceptual sense; this person truly believes in these statements. I heard these presented in a familiar, somewhat mocking way, as belonging to an uninformed, politically incorrect opinions of underprivileged community members, with an underlying message: this is what we are dealing with, so what to do to fix them?

I believe in innate human creativity. To me, that’s a fact. If not the statement itself, the belief in the statement is fact. If I was told this is wrong, or that I mustn’t believe or express this belief in public, for fear of persecution or marginalisation, well, I don’t know how I would feel about this. I accept that my belief sits amongst other beliefs that may or may not agree with mine, and that’s OK, for both me and society as a whole (as far as I’m aware!). So that’s what I’m with: how can we listen and include these minority voices in society? And I refer to them as minority voices, because I choose to believe they are a minority.

We seem to feel, in the media and on the whole, self-righteously that these statements are to be mocked, educated and possibly eradicated, for the greater social good. There’s a danger if we as a society, the greater community, do not listen; cannot find a way of some form of dialogue, where these voices are heard- not just seen to be heard- and then, only then, can we engage these voices with the other minority groups, and work on framing these beliefs alongside the majority’s. If all we’re doing is saying: you are wrong, politically incorrect, offensive, unhelpful etc. then we risk extremists in power dragging this section of society into a hole, where we cannot access them for a very long time, or ever.

At the particular area researched, at the aforementioned presentation, the researcher noted strong support for the BNP. I don’t believe that’s the reason for the statement, I believe the BNP and their equivalents, took the role of empathic listener. Whilst the majority, including the media, lumped this community as ‘white working class’, the BNP listened to them as unhappy individuals, as an integral part of the community, as people who need attention. And we all need attention when we are unhappy, so a Gold Star to the BNP. Yet, societies as a whole has made these unhappy citizens into easy prey for political party’s agenda, which can only benefit from pushing these statements further towards the extreme, and implement the beliefs into action.

I parallel this with extreme Islamic groups, like Al-Muhajiroun, who tap into unhappy youth, possibly as the name indicates, lacking a sense of belonging. Unhappy citizen is listened to, passionately fed a purpose, a way forward into a better world, their presence and contribution is celebrated…et voila! I’ve grown my beard, packed my backpack to Syria to do my bit for the world (be this, the The Hereafter).

I’m someone who was not born in the UK, arrived into this country barely speaking English, and belong to a faith that currently strikes fear into the hearts of the majority (and, inevitably, heavily featured in research on UK social relations at this weekend’s conference). And I’m moved to find ways of listening. Otherwise, those of us working on social relations simply become a club, preaching to the converted.

As well as listening, we need to find means of expression to incorporate what we have heard, to check if we have understood correctly, and then to express where we see ourselves standing.

On a micro-scale, in comparison to this spiel I’m on now, I found therapy ways of speaking helpful in adopting language that facilitates dialogue amongst people of difference in a workshop setting, for example, speaking from the first person, if I was to say: I find foreign people rude. Instead of dumbing the speaker with societal judgement, we can use this as a great basis for dialogue: Really? I want to know more, please, tell me more! What’s the story behind the statement? I ask myself: What’s my experience of ‘rude’? If that’s rude, what’s ‘polite’? I ask: Does your ‘rude’ match mine? Have you experienced me as rude?

We validate that experience by listening, and witnessing the distress, anxiety or fear that can be behind underneath the statement. We can connect on a human level.

The person making the statement may not need validation. We, those interested in including that particular person, need to validate their statement for ourselves as facts. The belief is a fact we need to take into account. This may not be the same kind of quantifiable fact as the hard evidence, the statistical data and objective conclusions I heard so much of at this weekend, but it is a truth. A true belief this person may want to act on, like I act on my belief in ‘innate human creativity’, and in fact, this is largely how I do what I do, because of that belief, as well as a whole host of other hippy dippy believes that I resiliently stand by. How can I hope to be listened to when I cannot listen to others?

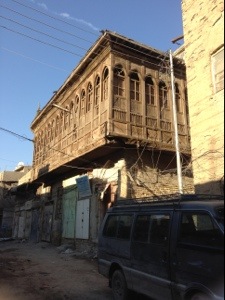

Whilst visiting family in Beirut, I was invited by a friend, Rabih Shibli, to visit one of the many Syrian refugee camps he and his team have been working on in Lebanon. Rabih runs a team at the department of Centre for Civic Engagement and Community Service (CCECS) at the American University of Beirut (AUB). I was curious to explore as I’ve wanted to run a pilot initiative for children there; workshops to service as an expressive and therapeutic outlet as well as instilling basic life skills relating to developing awareness of self and others, communication skills etc.

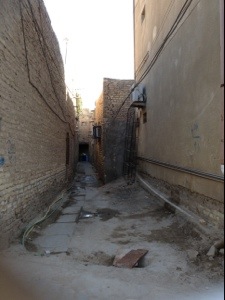

I joined a small CCECS team to De3naye Refugee camp in the Bekka Valley, stretching along the length of Lebanon to the East. As the team went about their business, checking-up on newly installed toilet cubicles (yet to function without running water) and registering family members for clothes distribution, I chatted to the kids. I wouldn’t go into the terrible conditions of the campsite, with no electricity, running water, simple tents with minimal isolation from the chill of the mountainous air. Nor will I go into the strain this refugee crisis has had on Lebanon’s already unstable political and economic state, and the intrinsic politics and competition between the many, many NGOs, and the non-existent communication between local governors and NGOs/ charities functioning in the region.

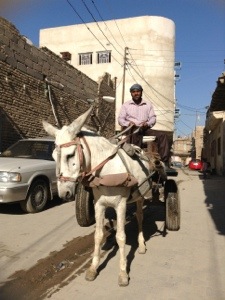

I just spoke to the children, who quickly congregated around the team. I asked where they played, and they took me to a vacant lot, just opposite the campsite. I asked if they would like to show me some of the games they played, and with no more encouragement, they excitedly played as I photographed and asked questions. I recognised some of the games from my own childhood in Baghdad, like the tunnel/ train: two form an arch (tunnel), and the rest make a line (train) to go the tunnel, at intervals the train is stopped as one child is captured and asked a question by the tunnel; in this case, the trapped child was asked ‘a bowl or a plate?’, and depending on the answer, the child went behind of the two forming the arch. When all the children had chosen sides, then the ends with a tug-of-war.

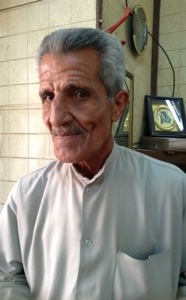

I enjoyed my position as an outsider, not just as a visitor to the camps, but also as an Iraqi. There has been tension in some of the camps, between the neighbouring Lebanese host communities and those from the camps.Because of my Arabic accent, I am immediately asked where I am from, particularly by the adults, so I was glad to steer away from choosing sides.

When talking to some to the adults. One parent, after tearfully sharing the difficulties she goes through on a daily basis, said: ‘We have so many foreigners who come over to take photographs and they promise this and that… and they all look so miserable. Their faces are so glum. So, if you don’t mind my saying, it is so nice to have you here, creating this merry atmosphere with the kids!’

I find it quite ironic that a refugee complains of the miserable appearance of their aid workers. This is why I find myself yapping on about my work being distinct from ‘charity’, as I feel the latter inevitably objectifies the very people targeted. There is an element of self-righteousness that I feel uncomfortable with. This inevitably applies to therapist-client and doctor-patient relationships. I work with those I want, and feel the need, to learn from. It is an exchange, a dialogue, and I hope, a valuable experience to be had by all parties involved. I trust that this is the attitude of the majority working in the Not-for-profit sector, and that my perceptions is more to do with public attitudes than those on-the-ground working on causes they believe in.

Nothing has come yet of my plans to work with these children, although I hear some of the biggest NGOs are about to put similar schemes into action, so that’s great news!

True Story.

…………………

Friend: By the way, I’m dating someone.

Me: That’s great! From work or on-line?

Friend: Neither really…

Me: OK. How long has it been?

Friend: Few weeks, I think. Actually, maybe four months.

Friend: Wow! Well done! That’s very encouraging news!

Friend: Yeh, well. You?

Me: No.

Friend: Yeh, you’re fussy. I’m trying to let go of my standards.

Me: Whatever you do, don’t tell her that.

…………………

End.

The fact that my own mother is a career mom has been eating at me, after my last post. This week, she won an ‘Architecture and Construction award’, for her tireless work in landscape design and eco-sustainability in the Middle East, and I am tremendously proud of her.

It is a pleasure to hold this pride. To recognise that my mother is not mine and my brother’s alone: she is her own person. We share her with her many students, of over thirty years of teaching in Baghdad and Beirut, and her many worthwhile projects.

My mother holds more respect for me, as an adult, than the majority of Arab moms for their ‘children’ (especially their daughters). She does not meddle and emotionally blackmail me to ring her daily- I phone because I want to- nor into getting married to manifest a brood, nor does she criticise what she does not understand. And these, largely, I put down to the fact that she has maintained possession of her own life. She has better things to do than attempt to live her life through me. And for this I am truly grateful.

Also, for eleven years, my single-parent mother did the job of three people, maintaining her teaching post, private practise and two kids. Pretty impressive, no?

And, yes, I was in a nursery from three years or younger, and in 1980’s Baghdad there were no dance or drama classes. Teachers kissed their favourite kiddies on the lips- my mother had to wipe lipstick off my face at the end of each day- and nap time took up three quarters of the day. I remember the misery of pretending to be asleep for what seemed like eternity.

As a child I felt the urgency of tasks, of the planned day to fit a grander scheme. We may have been an exception in Iraq, but here, a child’s day is scheduled to the brim. My happiest memories were of the rare and random, less-scheduled activities of pottering around in the garden, or helping in the kitchen. Even the night war sirens weren’t too bad, as these meant an escape from bedtime and extra time in our little family (including the dog), trapped in the basement for some ‘quality time’.

So the nursery kiddies here are privileged, as I was relatively in Baghdad, compared to today’s orphan and street kids all over the world (I’m thinking Basra, because of my short time there).

Rationale aside, I still feel sadness for the kids, whoever those may be, whose simple need for love is left half-met.

So in an attempt to get back into blogging, I’m doing a quickie whilst sleepless at 3am.

Much is fizzing in my head, and much has buzzed since my last obese-sized blog, though right now, I want to talk nurseries.

This week, with a friend’s drama company, I facilitated drama workshops at four different nurseries in London. It was to train me up as potential ‘sick cover’ and I agreed to do it part as favour, and part to experience something new. Until a few days ago, I’d never stayed in a room with kiddiewinks from 2 to 5 years old (I’d usually exit the space to preserve what little sanity I’ve held onto!).

It was fun. Fun and funny. Endearing, and at times, sickly sweet. Always with life’s brightness emanating from their little hungry eyes. Even those who- how shall I put it?- were a little more dreamy than bright, were just as wondrous. In so many ways, truly a life enhancing experience for me.

And anyone who knows me, knows I’m not a big kiddie person. I love and leave ’em, which is why I’ve not yet been tempted to pop a few myself.

However, what’s stayed with me, at the end of this week, is sadness.

Beautiful and unique creatures, every one of them, and yet, those who had brought them into the world, have chosen to hand them over to strangers for the majority of the day.

As far as I can tell, from my brief time at each nursery, the nursery staff were all well-meaning carers. Still, the trait most shared by the kids was neediness.

A need for attention, affection, and most of all, for love.

I was a relative stranger- at each nursery for one 30 minute session only- and yet at every stop, I had children holding my hand, wanting to share stories and to cuddle. How did they trust me so quickly, when I’d had so little time with them? Then I wondered, do they have a choice?

I read a postgrad Gestalt psychotherapy thesis on refugee children, in camps without their parents; it is common for those who have had to rely on the help and support of strangers to be less aware of personal boundaries, to repress the risks of entrusting at a very early stage, as most have had little choice in the matter. They have to trust to survive.

I wondered, does this notion apply to nurseries? The neediest children were so eager to please, be helpful and sweet. To make themselves as attractive to those strangers as possible. After all, mommy might love them, but mommy’s not here, so they best get on with whoever else is in control.

It struck me of little control these kids have. They are powerless.

Where are the parents? Is everyone out developing their careers? Precariously juggling motherhood on the corporate ladder?

These nurseries were not for those struggling financially, so I find it hard to imagine mommy and daddy are laying bricks to bring home a tin of sardines, whilst kiddies learned to dance, sing and be scary aliens (AKA drama).

And what about boarding schools from six years or younger? Is the brand name and education worth the price?

I am judging, which is unfair on many levels, and what I experienced this week felt unfair too. These kids may be a step ahead in our over-institutionalised world, and they will join the ranks of those who are left hungry for more. If the urges are not met now, at this early and fundamental stage, these kiddies will soon turn into searching adults.

At one nursery there was a mother with her two year old girl, and that seemed to strike an interesting pattern. The child was exposed to the goodness of being out in the world, whilst having her mom as a solid support (not just socially but physically too).

So these kiddies continue to search for love, I wish them a creative and fruitful journey, whatever they may find.

I want to come back to this blog, as the theme of boundaries, in the form of ‘containment’, has come back in my therapy process (probably, it never left!).

Self-support- knowing what I need and how to get it- is key in leading a healthy and fruitful way of being in the world. It can be as simple as recognising the feeling of being tired and being able to take adequate rest, to the ability to gauge how far to challenge yourself, when to say ‘stop!’ when you’ve had enough.

A month or so after my last post, I had a difficult, if somewhat traumatic, incident in my Gestalt therapy training. As an experiential course, and being new to psychotherapy, there is always a risk of misjudgement, be it from my or/ and the therapy tutor’s part. In my case it may have been a combination of both. I wouldn’t go into the incident here, except to say the theme of containment had a strong part to play there too; gauging how far I can go is part of my own self-support mechanism. Ultimately, it is my responsibility to say ‘Stop!’.

In my case, coming out of that period of painful recovery was a new lease of life. As I feel different, I see the world differently. This doesn’t become a Disney happy ending, and in fact, as long as I’m alive, the process never really ends!

I had a drastic haircut. It’s seemingly superficial, even a cliche, and yet a risk in itself.

And right NOW now, I have two final assignments for my course, which I am ridiculously behind in, as it reaches its end. I applied to do the one-year option, as opposed to the five year training as a therapist, and I admit I am tempted to continue to the second year. I know I do not want to be a therapist, as I agree with Fritz Perls in his criticism of the limitations of verbal articulation, and would want to leave more of the creative exercises to stand on their own merit, without being explained away in therapy. And yet, I am very tempted to do a second year, as I feel I have barely scratched the surface with Gestalt.

On a darker note, I always somewhat distrusted doctors, as I believe they need to de-humanise a patient to diagnose them; to see the pattern of symptoms, solve the puzzle and cure an illness. There are exceptions to this, and I enjoyed reading a transcript of Dr Barry Bub’s talk on integrating Gestalt in medicine http://www.processmedicine.com/presentations.htm.